Playskool Travel-Lite Crib (Part A)

Part A of the Playskool Travel-Lite Crib case discusses how the Travel-Lite came to market, details the deaths of three infants in the product, and brings Sanfred Koltun, CEO of Kolcraft, to a point where he must decide how the company will conduct a recall, as ordered by the CPSC.

Development of the Playskool Travel-Lite

Sanfred Koltun sat in his office in the Chicago headquarters of his company, Kolcraft Enterprises, reading a letter. Addressed to Bernard Greenberg, president of Kolcraft, the February 1, 1993, letter had been passed around to the company’s handful of top executives. He would get their perspectives on the situation. But Koltun knew that, as owner and CEO, he would be the one to determine the company’s actions. It had been this way since his father started the company in 1942.

The three-and-a-half page letter was from Marc J. Schoem, director of the division of corrective actions for the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). Schoem’s office, his letter explained, was responsible for making a preliminary determination about “whether a defect is present in a product and, if so, whether that defect rises to the level of a substantial risk of injury to children.”

“The CPSC has received reports of two infant fatalities resulting from the collapse of ‘Playskool’ brand portable cribs manufactured and distributed by Kolcraft,” Schoem wrote. “In both cases it appears the infant was entrapped when the crib collapsed while the infant was in the crib.” Schoem then requested a “full report.” Kolcraft would have to provide, among other materials, “copies of all test reports, analyses, and evaluations, including premarket tests and reports of tests and any analyses related to the locking mechanism and/or potential for collapse of product.” The CPSC also requested copies of all engineering drawings, any consumer or dealer complaints, lawsuits, assembly instructions in all their forms, and two samples of the Travel-Lite crib. Finally, Schoem noted, Kolcraft had a “continuing obligation to supplement or correct its ‘full report’” as new information about the product or incidents related to it became known.

Schoem closed his letter with the request that Kolcraft respond within ten working days.

History of Kolcraft

Kolcraft Enterprises was started in Chicago in 1942 as a manufacturer of baby pads, a foam product commonly used in high chairs, playpens, and bassinets. In 1950 Kolcraft began manufacturing mattresses for use in baby cribs. Sanfred Koltun, the founder’s son, graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the University of Chicago in 1954 and an MBA from the same school in 1955. He then joined the company, which at that time employed about 30 people.

By the early 1980s, Kolcraft diversified into the manufacture of various juvenile seats, including car seats and booster seats. Koltun opened a 25,000-square-foot facility in North Carolina making what are generically known as playpens, a metal and masonite folding device typically measuring 36” by 36” with mesh sides. Children would nap and play in these common household products. Kolcraft eventually expanded to include operations in Pennsylvania, Georgia, and California.

Kolcraft maintained a small executive suite with Sanfred Koltun as CEO. Kolcraft’s flow of information was informal, with meetings taking place frequently in a centrally located conference room at the headquarters.

In 1979, Kolcraft hired Edward Johnson, a graduate of a technical high school where he received training in draft work. Johnson had worked as a design draftsman for a lighting company, served four years in the Air Force, and worked for seven years at J.E. Industrial Molding as a designer in custom blow molding, a process that made plastic products with a cushion of air inside. He designed Kolcraft’s first car seat, which was sold in the Sears retailing chain, and by 1987 he had been named engineering head of Kolcraft. Johnson worked mainly on car seats and other seat products like high chairs until his first design of a portable crib, in 1989.

In 1987, Kolcraft hired Bernard Greenberg as a vice president. A graduate of New York University, Greenberg had worked at Macy’s for six years as a buyer, then spent a number of years with various manufacturers of juvenile products, eventually serving as president of Century, a juvenile product manufacturer which was a division of Gerber baby products. Greenberg became president of Kolcraft around 1990.

Development of the Playskool Travel-Lite

In the mid-1980s, the U.S. juvenile product market saw a substantial influx of imported goods, primarily from Asia, including a new product—portable play yards, or portable cribs as they came to be known. Rectangular in shape, the traveling cribs often folded into a carrying bag. Sanfred Koltun believed that Kolcraft could manufacture a similar, better product.

In the first half of 1989, Edward Johnson drew up some preliminary sketches for a portable, collapsible crib. Johnson’s design featured two hollow plastic sides that would serve as the exterior shell of the crib when it was folded for transport. The other two sides would be made of mesh supported by two collapsible top rails with a hinge in the middle. The solid floor would also fold at the center.

That spring, Sanfred Koltun gave the go-ahead to create a mock-up of the portable crib. “His comment from the very beginning was like it was the best thing he’d ever seen,” Johnson remembered later. “ It was unique because there was nothing out there with a carrying case. Nothing that was that structurally sound. Nothing that looked as nice as that."

Initial prototype models of the crib were heavier than Johnson had hoped — close to 19 pounds, as opposed to the 10 or 11 pounds he had originally planned. Nevertheless, the company’s optimism for the product continued. According to Johnson, the engineering department generated an “unbelievably thick” file on the Travel-Lite while trying to make the product achieve the portability that had been a major selling point of its competitors.

A Travel-Lite prototype was made and sat in the break room across from Johnson’s office in Bedford Park. Soon Johnson found himself demonstrating the crib to other Kolcraft employees. “We constantly were taking this thing down and putting it back up, kicking it around, because it was a unique product and everybody was … excited about it,” Johnson remembered. “Whenever someone walked into the room, they’d come in to me and say, ‘what is this?’ and I’d have to go through and explain it. And every time they asked, I’d tear it down and put it back up again. This thing [was] going up and down all the time."

A prototype model of the portable crib received a generally favorable reception from retail buyers at Sears, K-Mart, JC Penney, Wal-Mart, Montgomery Ward, Service Merchandise, and Target. Several buyers noted that they would like to see the crib be a little lighter. Some also noted that they had difficulty turning the crib’s locking mechanism, which consisted of round plastic knobs or dials located at the end of each top rail. “Some of the buyers told us they just could not turn the lock,” said Greenberg, who visited the engineering offices once a week to check on the project’s progress. “And [Johnson] kept on working on it."

The final design featured a nub on the outside portion of the dial that would slide into an indent on the inside portion. Once the crib was standing up, users would turn the knobs to the “lock” position (eventually designated by decals), and then hear a small “click” (Exhibit 1). “When we put it back to the buyers, they liked it a lot,” Greenberg said. “They thought it was a very good idea."

The crib would be ready for the trade show in Dallas.

Exhibit 1: The Playskool Travel-Lite crib with view of two side knobs.

Licensing the Travel-Lite

Sanfred Koltun believed that affiliating with a recognized brand name would be beneficial for Kolcraft. “I thought in terms of customers,” he said. “I wanted to get [our product] on the floor of juvenile departments in retail stores."

Playskool, well known in the juvenile products market for its reputation as a maker of high quality toys, was a property of the Hasbro company. Founded in the 1920s by Polish immigrant Henry Hassenfeld and publicly traded since 1968, Hasbro was in the 1980s one of the fastest growing companies in the nation, with successful brands such as Raggedy Ann and G.I. Joe, and revenues surpassing $2 billion. In 1983, Hasbro had hired John Gildea to be its director of licensing. Gildea had been employed by the owners of Hanna Barbera, where he had negotiated licensing contracts for such properties as the Flintstones, Scooby Doo, and Huckleberry Hound. Prior to 1983, licensing had not been a separate department at Hasbro, and top management at the company had directed the new department to find high-quality manufacturing partners who would uphold Playskool’s reputation in the marketplace. Through the mid-1980s, Gildea hired account executives to handle such properties as G.I. Joe, My Little Pony, and Mr. Potato Head.

By the end of the decade, Hasbro had begun licensing the Playskool name — a brand associated, as Gildea put it, with “quality, fun products."

The non-toy products are Playskool line extensions that we don’t happen to make. Our strategy is twofold. We gain incremental exposure of the Playskool name, [creating] brand awareness at a very early age that will pay dividends down the line. Secondly, and not insignificantly, it brings income. Licensing allows us to concentrate on our core business and also take advantage of the corporate name in appropriate products.

Both benefits looked relatively easy to achieve, and may have seemed necessary, as one of Hasbro’s main competitors, Fisher-Price, had already begun making products outside its traditional lines.

In the original agreement, Kolcraft would manufacture and distribute mattresses, playpens, and car seats with Hasbro’s Playskool name attached. The agreement stipulated, among other provisions, that:

[T]he licensee shall, prior to the date of the first distribution of the licensed articles, submit to the licensor a test plan which lists all the applicable acts and standards and contains a certification by the licensee that no other acts or standards apply to the licensed articles. … Test plan shall describe in detail the procedures used to test the licensed articles, and licensee shall submit certificates in writing that the licensed articles conform to the applicable acts and standards. Upon request by the licensor, licensee shall provide licensor with specific test data or laboratory reports.

Kaufmann helped with the final terms of the licensing agreement, and came up with one amendment: adding the new portable crib to the deal.

Going to the Show

Kolcraft’s display at the JPMA trade show in Dallas featured a separate area for its Playskool products, staffed by Kaufmann. The Travel-Lite received a warm reception, and a press release by the JPMA, dated September 15, 1989, named the Travel-Lite one of the top new products at the trade show:

At a press conference today, the Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association (JPMA) announced the winners of the “Ten Most Innovative Products Contest.”

A panel of independent judges … were instructed to judge on: creativity, originality, function, convenience, safety, innovative design, fashion, style, and overall appearance and use of the product.

Later, the crib even got some national press attention in the “What’s New in Design” section of the December 4, 1989, edition of Adweek magazine (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: The Playskool Travel-Lite crib in Adweek magazine.

Final Preparations

On September 28, 1989, Hasbro’s David Schwartz, who handled the Kolcraft account for the company, wrote a letter to Ernst Kaufmann, reminding him of Kolcraft’s obligations under the licensing agreement. “Pursuant to the terms of the contract between Hasbro and Kolcraft Enterprises, please be aware that Kolcraft must adhere to the terms set forth in Paragraph 7 (quality of merchandise), stating that: ‘The licensee warrants that the licensed articles will be designed, produced, sold, and distributed in accordance with all applicable U.S. laws.’"

On December 1, 1989, Kaufmann answered Schwartz with a letter, noting various government and industry testing standards that had been applied to the other juvenile products about to come to market under the Playskool name. For the portable crib, he noted only that the product would come with a one-year limited warranty. “My intention was to show that we had a quality product,” Kaufmann said later. “[One] that we were willing to put a warranty behind."

In subsequent conversations with Kaufmann, Schwartz again requested test plans for the Travel-Lite.

Dear Mr. Schwartz:

Please be advised that there are no government or industry test standards applicable to the Playskool portable crib.

We have therefore taken all reasonable measures to assure that this portable crib is an acceptable consumer product.

Very truly yours,

[signed] Ernst Kaufmann

Schwartz filed the letter.

Going to Market

Kolcraft began producing and shipping the Travel-Lite in January 1990. Both the crib and its packaging featured prominent placement of the Playskool name, and it was available in retail chains such as Toys ’R’ Us, KMart, JC Penney, and Wal-Mart. An instruction sheet for setting up the crib was affixed to the floor of the crib, underneath the mattress — “a standard production step,” Johnson noted. “It’s in the specifications for [conventional] play yards. … All the other play yards have them."

Sanfred Koltun was by now a proud grandfather. On family visits, his grandson would spend time in a Travel-Lite. “I was very happy with it,” Koltun said.

In June 1991, Edward Johnson received a patent for the Travel-Lite design. His petition noted that “the present invention relates to collapsible or foldable structures; and more particularly, to a collapsible structure suitable for use as a portable play yard.” Other play yards, the patent application contended, were difficult to fold, whereas Johnson’s design for the Travel-Lite was “easy to fold and transport."

Sanfred Koltun would later attribute the poor sales of the Travel-Lite to the fact that the crib was more expensive than similar imported items, causing discount retailers like K-Mart and Wal-Mart to shy away from the product. The design team felt that the product had simply become too heavy. “As far as the buyers go, [the] unit [was] too heavy,” Johnson said. “I don’t think it was the consumer. The buyers kept asking for more and more— more padding, things like that. And eventually, enough buyers said, ‘no.’"

Kolcraft ended up selling only about 11,600 of the cribs, models 77101 and 77103, and shipments stopped in April 1992.

The First Deaths

On July 3, 1991, an 11-month-old boy in California died of strangulation while in a Travel-Lite crib.

That spring, the report was mailed to Hasbro, which forwarded it to Kolcraft. In June 1992, Kolcraft responded with a letter to the CPSC, which stated in part:

The CPSC report on the July 3, 1991 incident involving a small child notes that the travel crib is subject to the voluntary standards of the juvenile products manufacturing industry. We note that there is no such standard applicable to travel cribs. The ASTM standard for play yards, ASTM F 406 does not apply to this product, which is a wholly different structural entity. Nor does the CPSC standard for non-full-size cribs, 16 CFR Part 1509, apply to travel cribs of this design.

The letter also noted that nothing in the report “suggests at this point that the Travel-Lite portable crib is defective in any way or presents a substantial hazard."

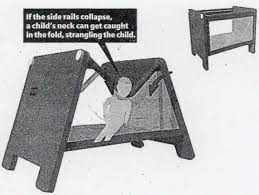

On November 30, 1992, a nine-month-old girl in Arkansas died when her Travel-Lite collapsed, strangling her in the “V.” A ten-month-old girl in California was killed in the same manner in another Travel-Lite on January 5, 1993.

The CPSC had only heard about two of the deaths when Marc J. Schoem wrote his February 1, 1993, letter to Kolcraft, requesting a full report on the Travel-Lite. Sanfred Koltun was shocked at the news. “I was appalled when I heard about the deaths,” he said. “I just couldn’t believe people were so careless."

Exhibit 3: The Playskool Travel-Lite crib in collapsed position.